— The true shape of the band that most concretely embodied rock’s era of becoming gigantic —

- 🎧 Listen to This Article (English / Japanese)

- Prologue: Why Led Zeppelin Is “Impossible to Skip”

- Chapter 1: The Night Before Birth — Before “Craftsmanship” Met “Wildness”

- Chapter 2: Formation — A New Ship Born from “The Yardbirds’ Embers” (1968)

- Chapter 3: Early Impulse — Using the Blues as Material to Build a Different Structure (1969)

- Chapter 4: Expansion — The Moment When Being Heavy Doesn’t Narrow Possibility (1970–1973)

- Chapter 5: The Peak — Zeppelin as an Encyclopedia (1975)

- Chapter 6: Modulation — The Cost of Gigantism and Making Peace with the Times (1976–1979)

- Chapter 7: The End — The Decision Not to Appoint a Replacement (1980)

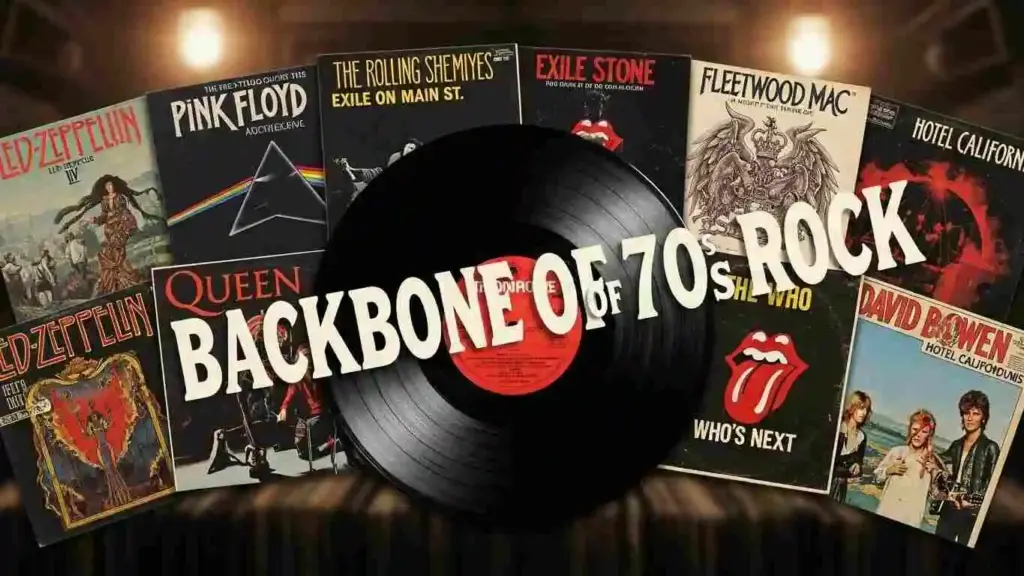

- Chapter 8: Legacy — The “Blueprint” Zeppelin Left Behind

- Closing: This History Article Is a Map to “Best 25”

🎧 Listen to This Article (English / Japanese)

This article is also available as an audio narration.

Rather than a simple biography, this is a story about how Led Zeppelin embodied

the moment when rock became culture, industry, and myth.

🇺🇸 English Narration

A roughly five-minute narration based on the structure of this article.

🇯🇵 Japanese Narration

The original Japanese narration, offering a slightly different rhythm and nuance.

Prologue: Why Led Zeppelin Is “Impossible to Skip”

If you’ve listened to rock for a long time, certain names eventually appear that you have to face on a level beyond simple “like or dislike.”

Led Zeppelin is the prime example.

They were not merely “a bundle of famous songs,” nor “a passing trend.” From the late 1960s into the 1970s, they presented—almost as a single model case—the process by which rock became a culture, an industry, and a myth.

And the tricky part is that Zeppelin is not an “easy band to talk about.” They’re often deified, yet they also carry—altogether—the light and shadow of 1970s rock: their distance from roots music (especially the blues), the issues of credit and quotation, gigantic tours and excessive living, the members’ physical and mental conditions, and accidents. That is precisely why they are worth writing about historically. And by organizing this once, the series that follows—my “Best Led Zeppelin (totally subjective)”—can become more than a simple popular-song list; it should make the background behind each pick visible.

Chapter 1: The Night Before Birth — Before “Craftsmanship” Met “Wildness”

The starting point of Zeppelin’s story is not the familiar “miracle of young talents naturally gathering.” At the center was less a charismatic star than a working professional—someone who knew the field.

Introducing the Members of Led Zeppelin

Jimmy Page: A performer—and an architect

Jimmy Page was born on January 9, 1944, in Heston on the outskirts of London, England.

Growing up in postwar Britain, he encountered music in a relatively stable home environment. From an early age he absorbed a wide range of sounds through radio and records, and as a teenager he became deeply drawn to the guitar.

What matters in Page’s musical formation is that, early on, he learned “playing that works on the job” rather than chasing “becoming a star.” In the early 1960s, as a session guitarist in London’s studio scene, he took part in countless recordings across genres—pop, film music, folk, blues. What those rooms demanded was not self-expression but the ability to deliver the required sound, reliably and quickly.

That experience shaped Page’s musical outlook at high speed.

Not just guitar technique, but:

- how to record sound

- what to fill, and what to leave empty

- how to maintain overall balance

—a way of thinking that always keeps the finished form in view—became second nature. In an era when rock was still young and valued momentum and spontaneity, Page was already the type who reverse-engineered the “completed work.”

After Led Zeppelin formed, Page led the band not only as guitarist but effectively as producer. In the studio he went as far as microphone placement and how reverb should behave, designing depth and weight with obsessive care. The uncanny three-dimensional presence of Zeppelin recordings—even compared to rock of the same era—makes sense only with that background in mind.

Yet Page did not remain merely a cool-headed architect.

On stage he pushed improvisation and impulse to the front. His live guitar was not a reproduction of the studio takes; it morphed in the moment, thrashed, and sometimes nearly collapsed. This coexistence—“controlled construction” and “unleashed impulse”—is the core of who Jimmy Page is.

Later, Led Zeppelin could:

- appear feral, like a wild beast, in concert

- while maintaining meticulous, layered architectural beauty on record

because Page was someone who carried both: the craftsman’s perspective forged through upbringing and work, and rock’s raw impulse that never left him.

Led Zeppelin’s gigantic presence was not an accidental aggregate.

It was also a structure built on the blueprint that Jimmy Page, the architect, had drawn through long apprenticeship and field experience.

Robert Plant: A voice that generates stories

Robert Plant was born on August 20, 1948, in West Bromwich in England’s Midlands.

He grew up near industrial zones and spent his youth in the particular atmosphere of postwar provincial Britain. From early on he was strongly drawn to American blues and folk, and was especially influenced by the passion and storytelling cadence of Black music.

What matters in Plant’s formation is not simply that “he could sing well,” but that he cared about “how a voice carries emotion.” His vocals put physicality and emotional tremor ahead of precision or neatness. That made his early singing rough at times—but it also gave it a ferocious magnetism.

Even before joining Led Zeppelin, Plant worked with local bands and forged his voice through live performance. The style of throwing emotion straight into the room—shouting his voice across the stage—was something built on the ground before it was refined in the studio.

Page saw possibility in Plant because the voice itself had the power to generate “story.”

In Zeppelin, Plant’s role was not merely that of a frontman.

His voice was an element that built the worldview on equal terms with the instruments.

Blues moans, folk lyricism, and rock’s open sky blended together; lyrics and voice fused to create a mythic atmosphere.

At the same time, Plant experienced both great joy and deep loss in his personal life. In 1977, for instance, he lost his son Karac. After that, his singing and the band’s work began to carry a different texture than youthful exhilaration—an undertone of loss and time.

Robert Plant was not only a defining rock vocalist of his era; he was the person who gave Zeppelin “narration” and “emotional heat.”

Without his voice, Zeppelin’s music would not have been passed down for so long as a “story.”

John Paul Jones: The musician who gave the music structure

John Paul Jones was born on January 3, 1946, in Sidcup (Kent), England.

He grew up in a family where both parents were involved in music, and received musical education naturally from childhood. For him, music was less an object of distant longing than something woven into daily life.

From a young age he studied piano, bass, and arranging, and he was also highly skilled at reading and writing music. As a result, he became a studio musician early—working not only as a player but also in arranging and behind-the-scenes roles.

Jones’s defining trait is not flash but the power to make the whole thing work.

Rather than adding more notes, he knows where to pull back and where to support. In Zeppelin—where strong personalities gathered—this quality was crucial.

In Led Zeppelin, he supported the skeleton of the songs, centered on bass and keyboards.

When the band expanded its musical range—folk-leaning pieces, acoustic settings, later material built around keys—Jones’s presence was indispensable.

Jones was not the type to push emotion excessively to the front.

That allowed him to grasp the flow of the music calmly and make judgments that kept the band from collapsing.

That Zeppelin could include long tracks and heavy improvisation and still hold together without breaking was, to a large extent, thanks to his sense of structure.

John Paul Jones was the quiet key figure who made Zeppelin “huge, and yet precise.”

Without him, the band might have been wilder—and shorter-lived.

John Bonham: Pure propulsion

John Bonham was born on May 31, 1948, in Redditch, Worcestershire, in England’s Midlands.

From childhood he showed an intense interest in percussion, and once he touched the drums, his talent quickly became obvious to everyone around him.

The hallmark of his playing was not delicate technique but overwhelming volume and forward drive.

Every hit was deep, heavy, and carried force that pushed the music ahead. His style was already established at a young age, and even on the local scene he was known as “the drummer who sounds different.”

He and Robert Plant knew each other from their hometown days and understood each other’s musical sensibilities well.

That trust became one reason why, after Zeppelin formed, rhythm and vocals locked together so powerfully.

In Led Zeppelin, Bonham’s drums were not just the rhythm section.

His playing determined not only tempo and mood but the breathing of the entire band.

The guitar riffs feel heavy, the performances surge forward—because Bonham is there.

At the same time, he was also someone who valued his family.

But fame, the pressure of life on the road, and brutal schedules gradually weighed on his body and mind.

This reality, too, symbolizes the light and shadow carried by 1970s rock.

After John Bonham’s sudden death on September 25, 1980, the band announced its breakup on December 4 of the same year.

Why they ended without appointing a replacement is clear.

Bonham’s drumming was not a replaceable part.

John Bonham was not merely Led Zeppelin’s drummer. He was their propulsion itself.

Chapter 2: Formation — A New Ship Born from “The Yardbirds’ Embers” (1968)

Led Zeppelin formed in London in 1968. The members were the four introduced above: Jimmy Page, Robert Plant, John Paul Jones, and John Bonham.

Behind that formation lay a reality specific to British rock at the time. In the late 1960s, it was not unusual for a popular band to break up while contracts and tour obligations remained.

As someone involved in the final phase of The Yardbirds, Jimmy Page had to take responsibility for such unfinished touring commitments. The Yardbirds were a major band within 1960s British rock, and their lineup shifted over time—an inherently fluid group.

The challenge wasn’t about keeping the name alive. It was that a new band capable of actually getting on stage had to be made real, fast.

Here, Page chose not a temporary patchwork but a lineup that could be musically sustainable. That decision is what bound together the four who would become Led Zeppelin.

What happened here was a fusion of professional judgment and a seemingly fated chemical reaction. Page handled “sound design,” Jones handled “structure,” Plant carried “story,” and Bonham carried “propulsion.” The division of roles is almost perfectly complementary. Even more important: though each had a fierce individuality, they didn’t simply step forward as solo personalities—they converted those forces into one gigantic, unified body called a band.

Chapter 3: Early Impulse — Using the Blues as Material to Build a Different Structure (1969)

In 1969, their debut album Led Zeppelin arrived. Then, with striking speed, Led Zeppelin II followed in the same year—a pace that itself reflects the era’s heat. Before drilling into the details of titles and track names, the core of early Zeppelin can be reduced to one point:

They did not “reproduce” the blues. They used the blues as “material.”

They brought in blues phrases, structures, and emotional coloration, then rebuilt them into something else through volume and sonic pressure, space, riff repetition, and the expansion of improvisation. This is where room for praise and criticism appears. In fact, Zeppelin has been debated for decades over credit issues involving roots songs. Whether one dismisses it as “theft” or understands it as “the customs and power dynamics of rock at the time,” evaluations split. For a historical article, what matters is confirming that this shadow is also part of Zeppelin, rather than mythologizing them alone. Neither pure praise nor pure condemnation reaches the real shape of gigantic 1970s rock.

At the same time, in terms of music history, the vocabulary early Zeppelin presented—“riff,” “sonic pressure,” and “live expansion”—went on to influence not only hard rock and heavy metal, but stadium-scale rock as a whole. What enabled that was Page’s sonic architecture, Bonham’s propulsion, and the sheer gravitational pull of Plant’s voice.

Chapter 4: Expansion — The Moment When Being Heavy Doesn’t Narrow Possibility (1970–1973)

Next, the band did not simply charge forward along the royal road of heaviness; they expanded their territory. The run of Led Zeppelin III (1970), Led Zeppelin IV (1971), and Houses of the Holy (1973) is easy to frame as an era-defining sequence even within the official discography.

The key point here is that Zeppelin didn’t “change direction”—they expanded.

- bringing in acoustic textures

- the shading of folk

- the construction of long-form pieces

- the pleasure of riff-centered power alongside an epic worldview

All of these coexisted—without becoming a mere collage. Why? Because the core was always the band’s sonic pressure and groove. In other words, Zeppelin wasn’t moving between genres; it was like adding new cities inside the same kingdom.

And in this period, two things solidified: album-mindedness and the live myth. Zeppelin preferred presenting a world in the unit of an album rather than chasing single-driven hit strategies. In concert, they would reshape songs, expand them, and update them into something else. Audiences weren’t going to see “reproduction”—they were going to witness an “incident.” The foundation was laid for rock to become a stadium-scale ritual, almost religious in its intensity.

Chapter 5: The Peak — Zeppelin as an Encyclopedia (1975)

Physical Graffiti (1975) is often described as the work that gathered Zeppelin’s “territory” into the vessel of a double album—positioned accordingly in the official discography.

Here they demonstrated that the elements they had built—blues, folk, riffs, epic atmosphere, groove, long-form construction—could be made to sound simultaneously, not as a simple retrospective but as living, parallel motion.

But a “peak” is also a turning point. A band that has grown too huge finds it hard to make the next move. After this, Zeppelin’s tensions increased—musically and in life. Beyond this point, we enter territory that cannot be described through shining myth alone.

Chapter 6: Modulation — The Cost of Gigantism and Making Peace with the Times (1976–1979)

The stretch that leads through Presence (1976) and toward In Through the Out Door (1979) overlaps with the “late stage” air of 1970s rock, and the official discography lines these works up clearly.

Post-punk shifts, changes in the music industry, changes in audience values—facing such external transformations, Zeppelin did not adapt by becoming “a different band.” They chose instead to remain Led Zeppelin.

This is where opinions diverge. Some see maturity; others see stagnation. Historically, what is certain is that they never let go of their “core.” That core was sonic pressure and groove, the band’s unity as a single organism, and the very fact of being “gigantic rock.”

And in this period, another reality becomes visible: Zeppelin was tied not only to individual talent, but to life, bodies, touring, and the industrial structure around them. The cost of rock becoming huge appears outside the sound as well. That is why Zeppelin should be discussed not only as music history, but as rock cultural history.

Chapter 7: The End — The Decision Not to Appoint a Replacement (1980)

In 1980, after the death of John Bonham, Led Zeppelin disbanded.

This is what makes Zeppelin’s story special. For a band of their magnitude, there was a path to continue by appointing a replacement. Rock history offers examples of that. But Zeppelin decided that without Bonham, it would not be Zeppelin—and they ended it.

This is less a sentimental “beautiful story” than proof that Zeppelin was “one propulsion system made of four people.” Page’s design, Jones’s structure, Plant’s voice, Bonham’s drive—remove one, and it becomes a different ship. The band themselves understood that reality better than anyone.

Chapter 8: Legacy — The “Blueprint” Zeppelin Left Behind

When we talk about Zeppelin’s influence, stopping at sales figures and legendary anecdotes makes the story thin. Their greatest legacy is a concrete “blueprint.”

- A philosophy of sound-making

The pressure of the guitar, how to record drums, how to use space. The idea that the studio is not merely a recording device, but a place to construct a work. - Album-mindedness

An attitude of presenting a worldview in the unit of an album, rather than focusing on singles. The major studio works from 1969 to 1979 lined up in the official discography function almost directly as the “spine” of 1970s rock.

- Updating songs through live performance

Aesthetic not of reproducing recordings, but of reshaping and renewing songs into something else on stage—giving enormous propulsion to the movement in which rock became a kind of stadium ritual. - How to handle roots (including both light and shadow)

Using blues and folk as materials and transforming them into gigantic rock. That process was innovation—and it also invited criticism and debate. Zeppelin is a symbolic presence that carried both sides. Keeping this unblurred is what makes a historical article honest.

Closing: This History Article Is a Map to “Best 25”

Everything written here, in the end, is not for “telling the myth.” On New Year’s Day, January 1, I’ll begin “My Totally Subjective Best Led Zeppelin”—and this is a map so that it won’t become a simple popularity-based song introduction.

- Why the raw brutality of the early period pulls at us

- Why the expansion-era albums feel like a “kingdom”

- Why the later modulation starts to carry the texture of life itself

- Why Zeppelin feels “complete”

When you listen to Zeppelin, the points that attract you can change depending on the period. There are moments when the early wildness grips you hard; other times the expansion-era body of work feels like a single kingdom. With more time, you may even find in the later modulation a texture of life you didn’t notice when you were younger.

And ultimately, why Zeppelin is spoken of not as “unfinished,” but as a “completed existence”—that reason also becomes clearer within this flow.

With this map, each selected song gains a reason—“why it sits there.” Rankings gain persuasion, and even the songs left out retain meaning. Above all, when I rewrite this project again years from now, I feel I’ll be able to describe a different landscape on the same map.

コメント